Monitoring Necurs - The tip of the iceberg

Anubis Networks began monitoring Necurs, a malware family known for it's rootkit capabilities, in August 2015. Since then we have been able to observe approximately 50.000 unique IP addresses connecting to our sinkhole over a 24 hour time period. However, we recently discovered that we were only seeing a small part of the whole botnet.

Necurs’ rootkit capabilities include both a user mode and a kernel mode component, making it a very capable piece of malware that is able to tamper the system at the lowest level.

Necurs is commonly installed by other families of malware (e.g. Zeus, Dorkbot), but reports show that it can also be distributed on its own using exploit kits. Once it gains access to a system, it is able to steal user information, install additional malware or send spam.

One particularly interesting feature of this malware is its C2 (command and control) channels. To ward off takedown attempts, Necurs uses several techniques simultaneously:

- HTTP using a list of hardcoded servers

- HTTP using a server obtained through a DGA

- A custom P2P network that is used mainly to deliver lists of HTTP C2 servers

To make itself difficult to monitor, the malware uses an algorithm that converts the IP addresses received through DNS to the real IP addresses of its servers. This means that in order to successfully sinkhole the malware, the algorithm needs to be reversed.

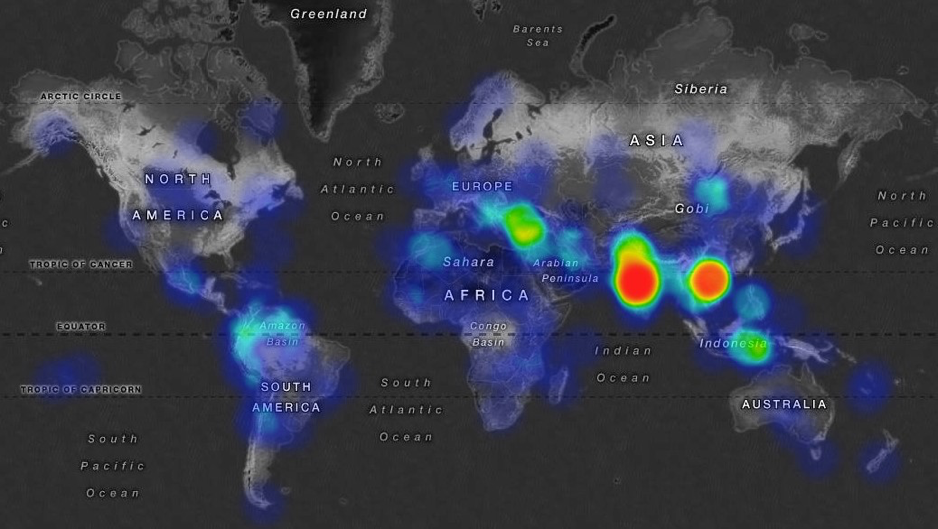

While Necurs-infected systems are present in most countries in the world,most infections exist in Asia, with a particularly strong presence in India. The following map shows the worldwide distribution of the infection.

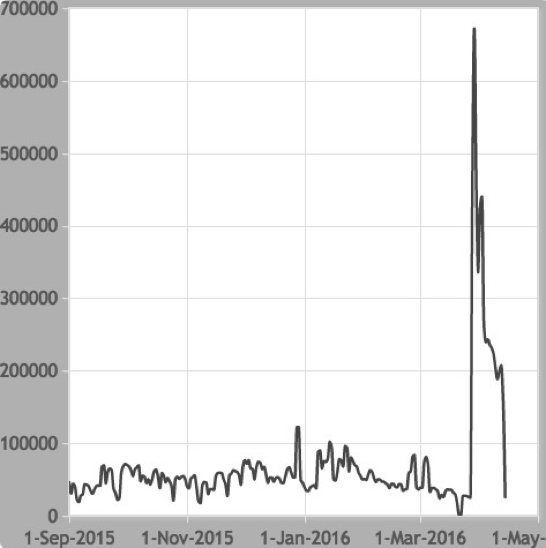

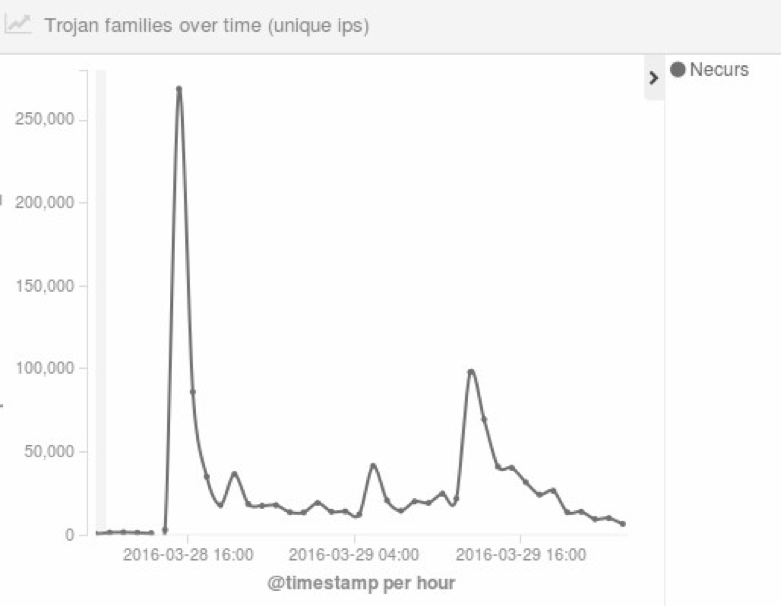

For several months, the total number of infections in a 24 hour period averaged around 50.000 IP addresses, but this number was slowing decreasing over time. However, on March 28th, 2016, we saw a sudden spike in the count of infections: the number of IPs connecting to the sinkhole over a 24 hour period reached over 650.000. Over the next few days, this figure steadily dropped until it reached the usual infection count.

As we started searching for an explanation for these new connections, we assumed that the drastic spike to 600.000 infections in one day would get a lot of attention through open source intelligence or media channels.. However, this was not the case, and we could not find any clues through OSINT. We decided to look at the malware again and briefly review the way its network communication channels operated..

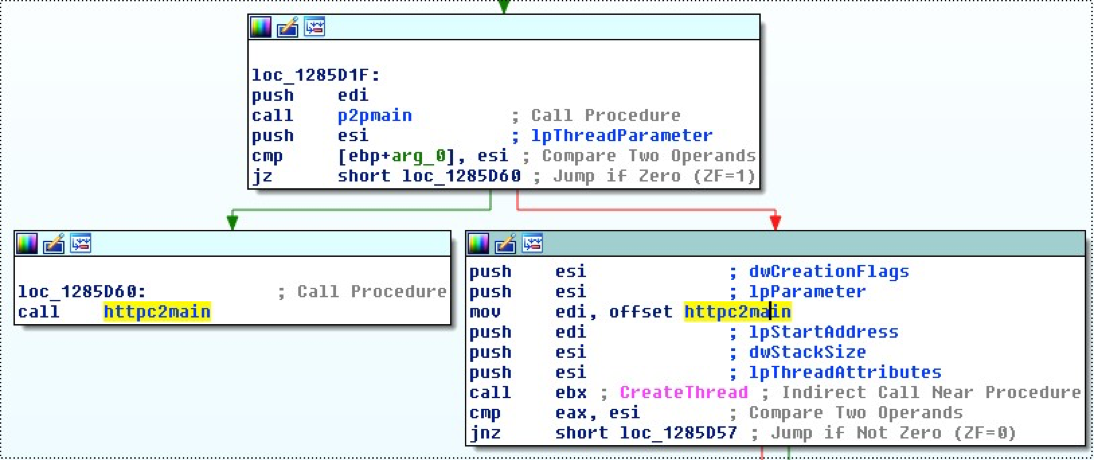

When the malware is executed, it starts its P2P connection routine (called p2pmain in the image below) and then calls the HTTP command and control routine (called httpc2main below) directly or in a new thread (in case the malware is started as a service).

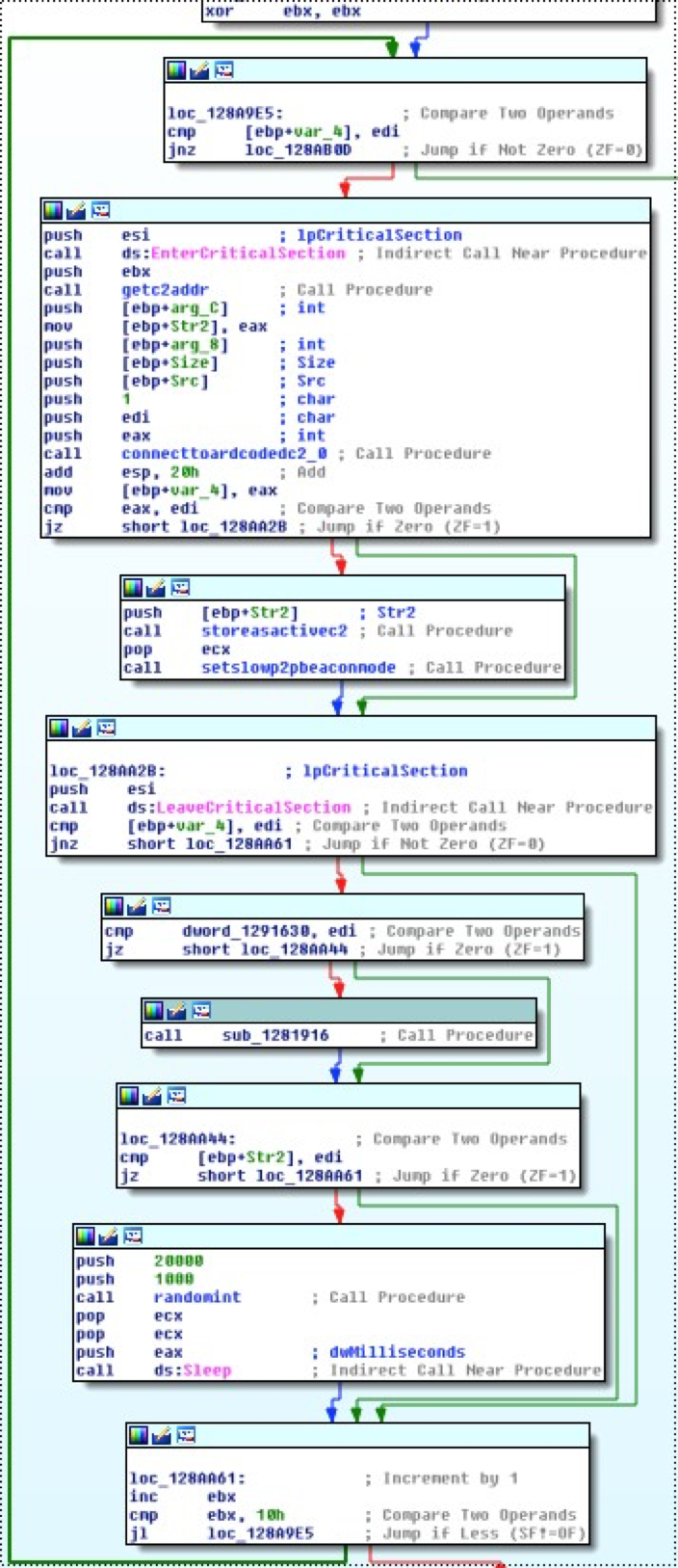

Once the execution reaches the HTTP C2 connection method, the malware receives the IP address of a C2 (using the function called getc2addr below) and attempts to connect to it. If the connection is successful, it stores the address on a global variable (using the function called storeasactivec2 below) that will be returned by the getc2addr method on the following connection attempts.

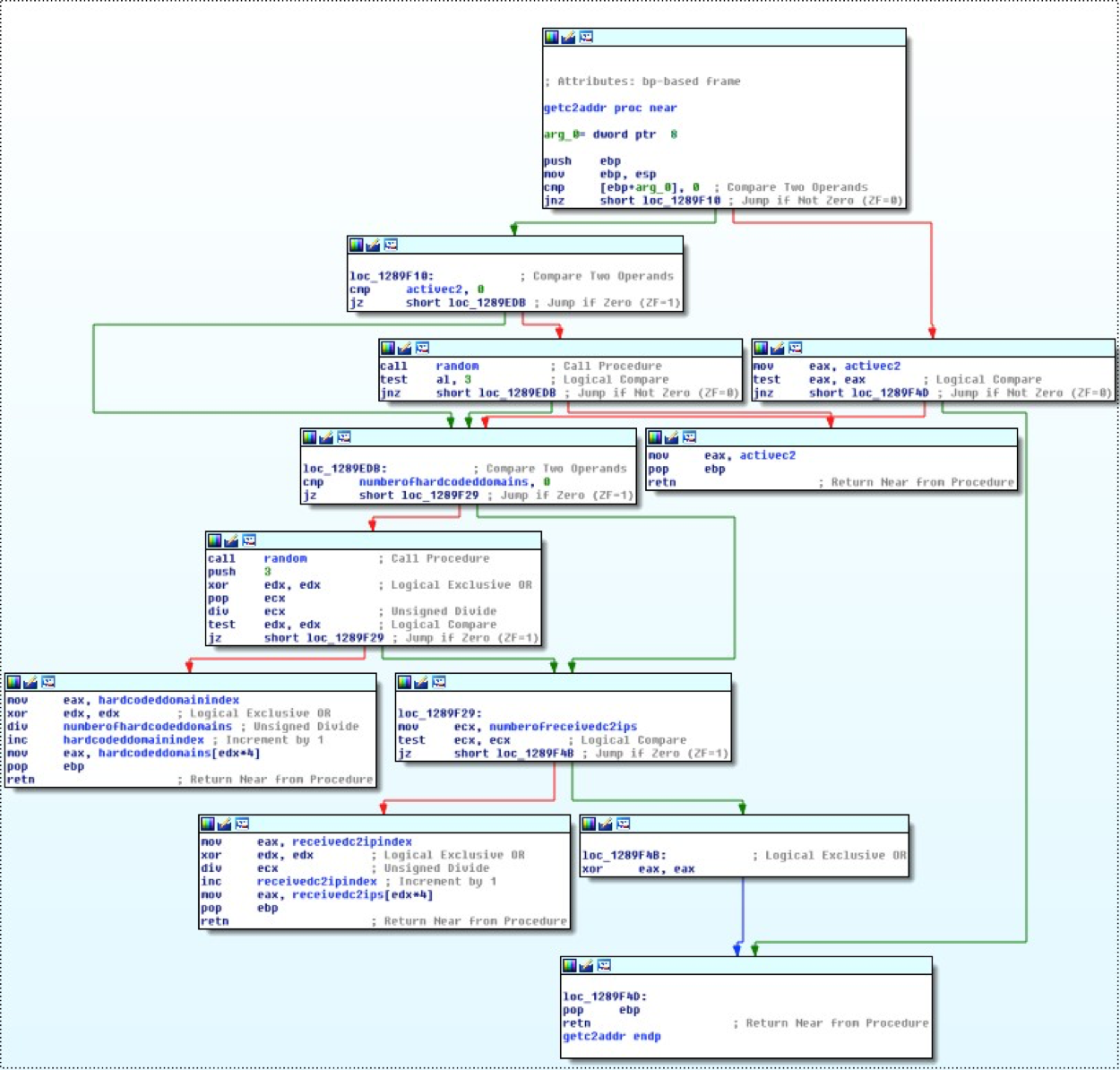

The following image illustrates the getc2addr function. If an active C2 exists, the function always returns the active C2 address (arg0 is always 0 on the first connection attempt). If not, the function will return a hardcoded address, or one of the addresses received through the P2P network.

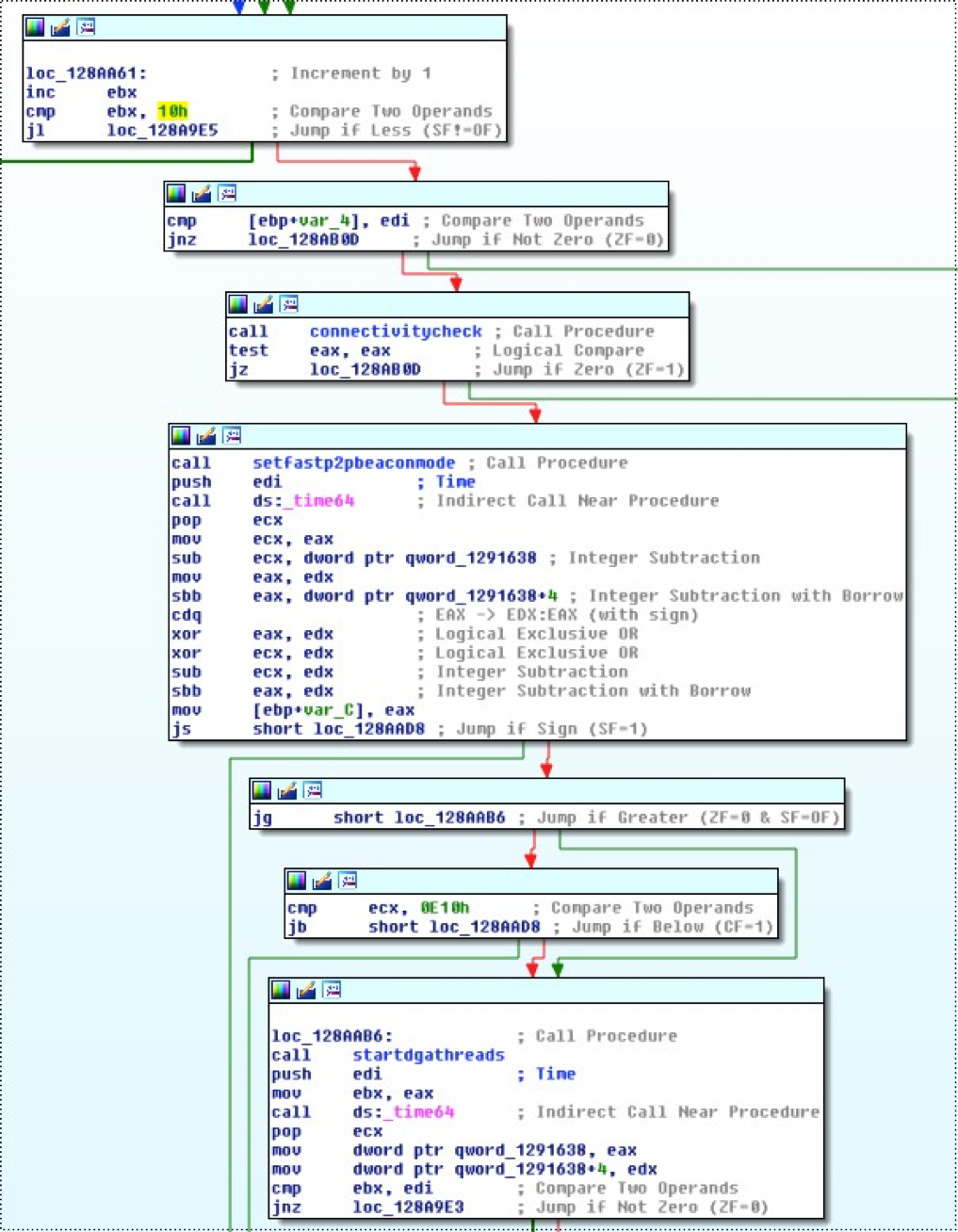

If the C2 connection attempt fails 16 times, the malware will run a new connectivity check (connecting to Microsoft or Facebook and four randomly generated domains), set the P2P network beacon to a high frequency, and start the real DGA, as shown below.

If the malware finds a real active C2 through the DGA, it will add it to the active C2 global variable and continue connecting to it in the future.

After a brief analysis, we observed that an infected system would only connect to our sinkhole until it found a real active C2 server through its hardcoded list, the DGA or the P2P component. After that, it would only communicate with that same active C2 server (and no longer reach our sinkhole) unless one of the following actions occurred:

- The real C2 stopped responding;

- Thesystem was shut down or hibernated;

- The local network was disconnected.

At this point we determined that the daily average of 50.000 IPs we observed was just the tip of the iceberg, and the Necurs botnet was actually much larger.

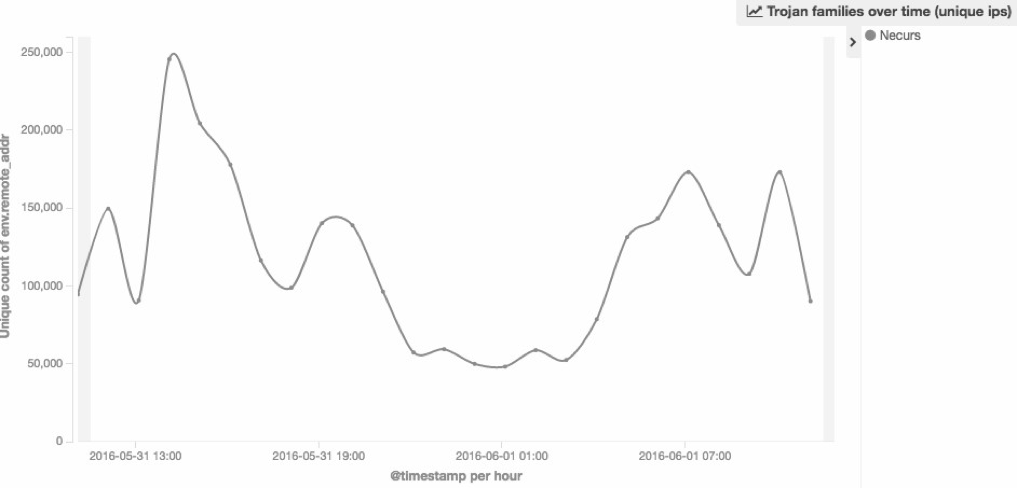

Looking closer at the sinkhole connections on the day of the spike, the following chart shows how many different IPs reached our sinkhole during each 1 hour interval.

The chart demonstrates that the connections came in spikes, which suggests that the real C2 went offline a few times throughout the day. When it disconnected, the bots began looking for new C2s, causing them to connect t to the sinkhole and result in the spike of connections that we observed.

To confirm this theory, we left an infected system running in a controlled environment for an extended period of time. We were able to see that it lost connectivity to the active C2 and started searching for new C2’s. At the same time of the lost connection, we observed a new spike of a few hundred thousand connections to our sinkhole.

So, how big is this botnet? Based on the number of IP addresses connecting to our sinkhole per day, we know that it has more than 650.000 infections. After looking at the chart that shows the first spike, we believe that if the real C2 had not come back online this number would have been considerably higher, making the Necurs botnet one of the biggest active botnets today.

That’s it for this blog post! Keep posted for new developments.

For more information about the Necurs Botnet, check out these interesting reads:

- https://www.virusbulletin.com/virusbulletin/2014/04/curse-necurs-part-1

- https://www.virusbulletin.com/virusbulletin/2014/05/curse-necurs-part-2

- https://www.virusbulletin.com/virusbulletin/2014/06/curse-necurs-part-3

- https://www.johannesbader.ch/2015/02/the-dgas-of-necurs/

- http://www.malwaretech.com/2016/02/necursp2p-hybrid-peer-to-peer-necurs.html

- https://www.microsoft.com/security/portal/threat/encyclopedia/entry.aspx?Name=Trojan:Win32/Necurs

Update 2016-06-01:

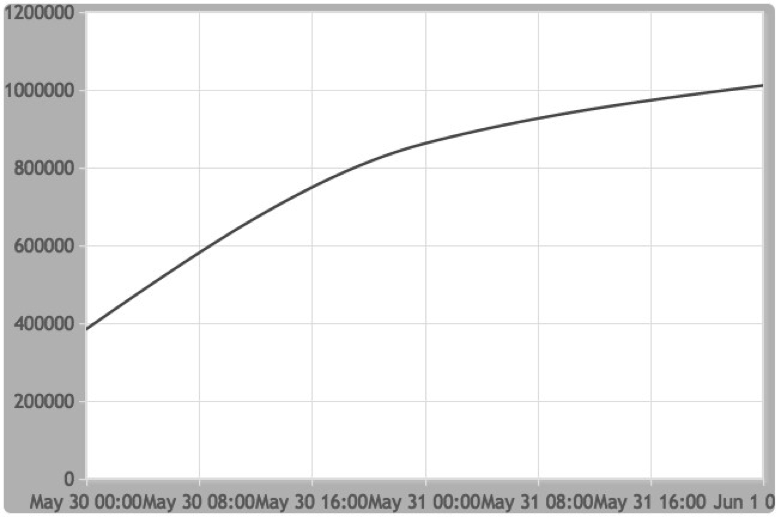

Only one day after publishing this blog post, the Necurs C2 went offline for 24 hours straight and we were able to see the whole botnet. In the last 24 hours we have seen over 1 million bots (1.091,024 unique IP addresses) connect to our sinkhole.

The following graph shows the number of unique IPs over a 24 hour window:

The following graph shows the number of unique IPs contacting the sinkhole during each hour:

This 24 hour window was a great chance to see the whole botnet and to confirm that, with more than one million bots, Necurs is one of the biggest botnets active today. Keep posted as we find out more about this botnet!